I often wake up in the morning with a particular song stuck in my head. It’s a song that has come to mind most of my life, and I always enjoy mentally rehearsing the lyrics…

I sit in my old car, same one I’ve had for years/

Old battery’s running down, it ran for years and years/

Turn on the radio, the static hurts my ears/

Tell me where would I go, I ain’t been out in years/

Turn on the stereo, it’s played for years and years.

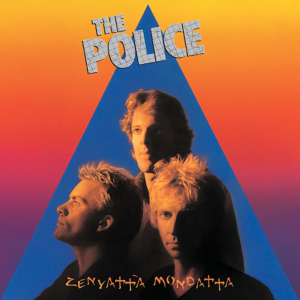

When the World Is Falling Down, You Make the Best of What’s Still Around by The Police was one of my favorite songs in high school and regularly cued up in my tape deck. (Yeah, I’m that old!) I had a new car, and I was constantly cruising around town – thanks to my dad’s “unrequited love” for a Nissan 240SX in college. I was hopeful and naïve, skinny and pimply, with a teenager’s typical melancholic disposition.

Whenever I played this particular track, however, I felt my adolescent frustrations drift away. The blend of Andy Summer’s shimmering guitar chords and Stewart Copeland’s metronomic beat measured against Sting’s syncopated bass line and near-nasally voice was an aural antidote. Never mind that the lyrics didn’t reflect my life at the time. Something about them just made perfect sense, like I knew that my life could easily turn into the song.

I never would have guessed I would be singing the same song 30 years later … with more heart and soul than ever before.

“Tell Me Where Would I Go?”

I have been out of work for over a year now. I resigned from a position that wasn’t the right fit for me. I began applying for jobs a few months before I resigned, had some promising interviews, and continued to pursue interesting leads.

The time off was great those first few months. We didn’t yet know how dire Covid was, so I traveled to a cabin in northern Minnesota to play in the snow. I joined friends in Sedona, Arizona, to ride mountain bikes, then took a trip to Portland, Oregon, to visit my brother and do some beachcombing on the Pacific Coast. When the pandemic forced cities and states to lock down, I used social distancing to my advantage to go hiking, cycling, and camping. I kayaked and swam.

I did all of this while applying and interviewing for job after job, knowing that something would eventually pop up. I would get an occasional phone interview but no follow-up. I started feeling sorry for myself.

But I had distractions. My kids, ages 10 and 13, were distance learning at home, and my de facto job as the unemployed parent was to hold down the fort and serve as their proctor. It was rough at first – lots of yelling, meltdowns, and sulking – but we eventually slipped into a routine. I would focus on job applications while the kids struggled to pay attention during virtual classes.

Summer came and went, distance learning resumed, and I started to worry. I had submitted more than 60 applications since my resignation, half of which resulted in rejections and half of which got no response. These weren’t routine applications, either. Several required extensive essay responses ranging from 2,000 to 3,000 words. Some required the creation of marketing collateral and a presentation. In one instance, during a second interview, I pitched an idea for promoting a public service campaign, only to see my idea – almost exactly as I had pitched it – implemented on social media a few weeks later.

The demand for professionalism during the application and interview process, countered by the subsequent disregard for my experience or effort, began to take a toll on my mental health in early fall. Any positive thoughts I had were repeatedly drowned out by doubt and negative self-talk. I questioned my worth and very existence.

The winter of my discontent had arrived. Shorter days and darker, colder Minnesota nights cloaked me in depression. The upbeat Police anthem that normally popped into my head and flipped my attitude was replaced by lyrics from Sting’s The Hounds of Winter. Riffing on the lines, I was as dark as December and as cold as the man on the moon.

“Do What You Can, With What You Have, Where You Are”

When I’m feeling especially depressed about my unemployment, I take a bike ride or walk my dog, Oscar. A mile from my house, there’s a park with a small lake and a few baseball fields where I play fetch with Oscar. I usually listen to a podcast or an audio book on the way there and back.

During one recent outing, I listened to a Hidden Brain episode titled Minimizing Pain, Maximizing Joy. The host, Shankar Vedantam, was interviewing philosopher William Irvine about the advice posited in his book, The Stoic Challenge: A Philosopher’s Guide to Becoming Tougher, Calmer, and More Resilient. Irvine urges listeners to embrace the wisdom of Stoic philosophers as a method of mitigating challenges. He sums up the Stoics approach to life with a pithy platitude: “Do what you can, with what you have, where you are.”

The Stoics, who are typically, and incorrectly, regarded as emotionless people, were usually quite joyful, according to Irvine. It was their control over their emotions, opinions, and actions that gave them the freedom to live in the moment and enjoy their surroundings, regardless of the circumstances. Philosophers like Epictetus teach us to be happy in the face of adversity, Irvine explained.

Epictetus (50 – 135 AD) was born a slave and eventually freed after the death of Nero. He was banished from Rome alongside the city’s other philosophers by Emperor Domitian and went to live in a remote village in Greece. Despite the area’s limited resources, he made the most of his circumstances. He found a fresh spring that was previously undiscovered by villagers and established a philosophy school.

Philosophy was a way of life for Epictetus. According to his teachings, we have no power over the external, only power over our own actions and perceptions. He advised his students not to waste time and energy worrying about or resisting what they could not change, but instead, to train their minds to be free of judgments, to prepare themselves for difficult times and insults, and to not be conceited.

That advice may seem like common knowledge now, but during a time of megalomaniacal emperors and melodramatic political conspiracies, it was groundbreaking – mostly because it encouraged people to think for themselves and rise above their situations.

Epictetus’s teachings have inspired many great minds over the centuries, too. His writings motivated Marcus Aurelius to remain a kind and generous emperor during a long pandemic and constant wars. Shakespeare, Rabelais, James Joyce, V.S. Naipul, J.D. Salinger, and Tom Wolfe all paid homage to Epictetus in their writings. President Teddy Roosevelt carried Epictetus’ Dialogues with him on his treacherous trip through the Amazon, and retired Navy Vice Admiral James Stockdale kept a copy on his missions as a fighter pilot during the Vietnam war. Stockdale later claimed that Epictetus’ teachings helped him endure the seven and half years as a prisoner of war.

Sting Versus the Stoics

So, what’s the connection between Sting and the Stoics? For me, both have helped me to temper my inner monologue when times are tough. Sting’s clever lyrics help me shift my focus away from my specific shortcomings to universal situations, while the Stoics’ sage advice equips me with mental practices to counter bouts of despair and self-doubt.

There’s also a great pun that coincidentally connects the two. In Irvine’s study of Epictetus, he coins the phrase “sting-elimination strategies” to describe the mental exercises Epictetus invented to counter insults. Here are five ways Epictetus advises us to respond to insults:

- Pause and consider if the insult is true.

- Consider the source of the insult and how well-informed that insulter is.

- Question the competence of the insulter without being defensive.

- Remember that it’s not the person who is insulting to us but our perception and judgment of the insult – both of which we have control over.

- Refuse to respond to an insult or respond with humor.

Being rejected for jobs is incredibly insulting, in my opinion. But it’s just that: an opinion. I can choose to grovel over my circumstances like the central character of Sting’s song, or I can put this valuable time to good use by building my intellect. I choose the practicality of the latter, while appreciating the poetry of the former.

Epictetus liked to ask his students, “How have you made progress?” Since I’ve been out of work, I’ve made progress by reading and learning … about philosophy, about politics and society, about myself.

What about you? How have you made progress during the pandemic? Maybe it’s time to make the best of what’s still around by reading – and thinking – like the Stoics.

This essay originally appeared on LinkedIn.