My story begins in the land of the Ojibwe and Aandeg the Crow, in a state of absolute serenity . . . a quick weekend trip to the middle of Minnesota, where miles of mountain bike trails freshly blanketed in snow unfurled before me. My face, the only part exposed to the cold air, stung slightly in the breeze as I pedaled the groomed, cloud-like path on my blaze-orange fat bike. Four pounds of air in each tire flattened against the soft-packed snow. The air was perfectly quiet and still.

Cruising along the snowy singletrack, my mind drifted to the story of Aandeg. According to legend, Aandeg the Crow was without purpose. During the creation of all the “flyers,” the Great Spirit gave a unique purpose to the eagle, the hawk, and the loon but not the crow. So, Aandeg flew around searching for his purpose, seeking out other animals for guidance, but he found no purpose from what they taught him. Continuing his search, Aandeg responded to the cries of other animals in distress, first a squirrel feeling “sad and drained of life,” and then a rabbit who wanted to die it was so tired of being chased by the fox. Aandeg used the knowledge he had gleaned from others to advise the squirrel and the rabbit and restore hope in both. The legend soon spread that Aandeg found his purpose in helping others find or renew their purpose. “Aandeg is our traveling companion always reminding us that . . . [w]e cannot find our purpose if we sit on the path,” the story goes on an Ojibwe language and culture website. “Crow teaches that you must meet life head-on and create good connections with those around you and work with spirit of friendship.”

That was my state of mind as I drifted blissfully along the trails, silently questioning my own purpose and whether I was on the right path. For years I had been visiting the Cuyuna Country State Recreation Area, a remediated mining region, to ride my bike and unwind at the Red Rider Resort in Crosby. Only a two-hour drive from Minneapolis, the area has become a popular mountain-bike destination for cyclists in the Twin Cities and beyond. More than 50 miles of easily accessible trails invite riders of all abilities to flow smoothly along their compacted iron-oxide soil—a red ochre so vigorous that the proprietors of the resort placed laminated cards on the plastic mattress covers demanding that guests bring their own fitted sheet to avoid staining the beds and being charged a steep fee for the damage.

Rolling along trails under towering evergreens and past deep, emerald lakes is a restorative experience, a chance to be rehabilitated by nature as fully as the landscape was rehabilitated after the mining industry moved out. In winter, the place is a sanctuary where hoar frost shimmers like shivering angels in the atmosphere and ruby-red cardinals sing hymns to the solstice.

The land was once home to the Mille Lacs Band of the Ojibwe, now relegated almost entirely to Mille Lacs County, a unique and sovereign, federally recognized tribal government territory. The native inhabitants described their home as the place “where the food floats on water” in recognition of the region’s ample wild rice beds.

My original plan was to visit Cuyuna the first week of February, to make the most of the seasonal snowfall, but the day before I was set to leave, my car was stolen from my driveway. The car was a Kia, and those were being swiped daily by roving bands of teens calling themselves the “Kia Boyz.” The novice car thieves stole cars with the simple insertion of a USB cord behind the ignition. They would film their grand theft auto and joyrides with their smartphones then post them to TikTok. Their following grew by the thousands. When my car was recovered on a nearby side street a day later—the inside trashed with crowbars, bags of new cotton warm-ups, copper wiring, and, strangest of all, a battery-powered vacuum cleaner—I knew it had been swiped by a pro and not a bunch of wannabe gangsters. The ignition was bored out with a drill, and the sockets, wrenches, and assorted tools left behind suggested the thief knew what they were doing. Insurance would cover the damages, but it did little to assuage my discomfort at having my main mode of transportation so easily swiped and my plans for a therapeutic fat-bike getaway thwarted.

Already prone to a serious case of weltschmerz, I often reacted to life’s injustices fatalistically, waiting for one random mishap to knock down the next existential domino. I had experienced a series of misfortunes in the five years since my family and I sold our house in Kansas City and moved to Minneapolis. My wife lost her job less than a year after we relocated . . . that job being one of the main reasons we uprooted our lives. Then, like a fool, I quit my job two months before the COVID-19 pandemic hit because my boss decided to pursue an ill-conceived plan to restructure departments. Little did I know that it would take me nearly two years to find another gig, despite 20 years of experience and sending out more than 150 resumes. The constant rejections and consequential instability left me simmering with anger and hostility and consuming ridiculous amounts of whiskey and beer, all of which threatened my struggling marriage. When George Floyd was horrifically murdered by Derek Chauvin in May 2020 and the city went up in flames, the weight of the world seemed to grow infinitely heavier. The temperature of my anger rose from a simmer to a boil at the system of oppression that so flagrantly murdered Black citizens with alarming regularity and disregarded the basic human rights of its citizens. So, nearly three years after Floyd’s murder, when my as-yet-unpaid-off car was stolen from the alley driveway just four blocks from George Floyd Square, I was primed and ready for a fight . . . with criminals or cops, it didn’t matter which.

Searching for a New Perspective

The air in the woods that day was invigorating, the snow perfectly groomed, and my spirits at an all-time high. It was early on a Friday, and I was the only person on the trails. All was right with the world. In my reverie, time slipped away, and I cruised 10 miles before hunger had a chance to catch up with me. I was feasting on endorphins and completely forgot that I started my ride on an empty stomach. Succumbing to intensifying hunger pangs, I cruised back to the cabin, changed into street clothes, and drove into town.

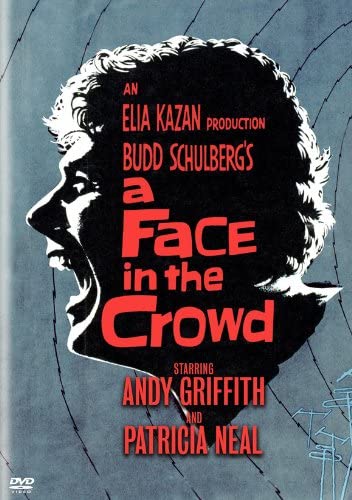

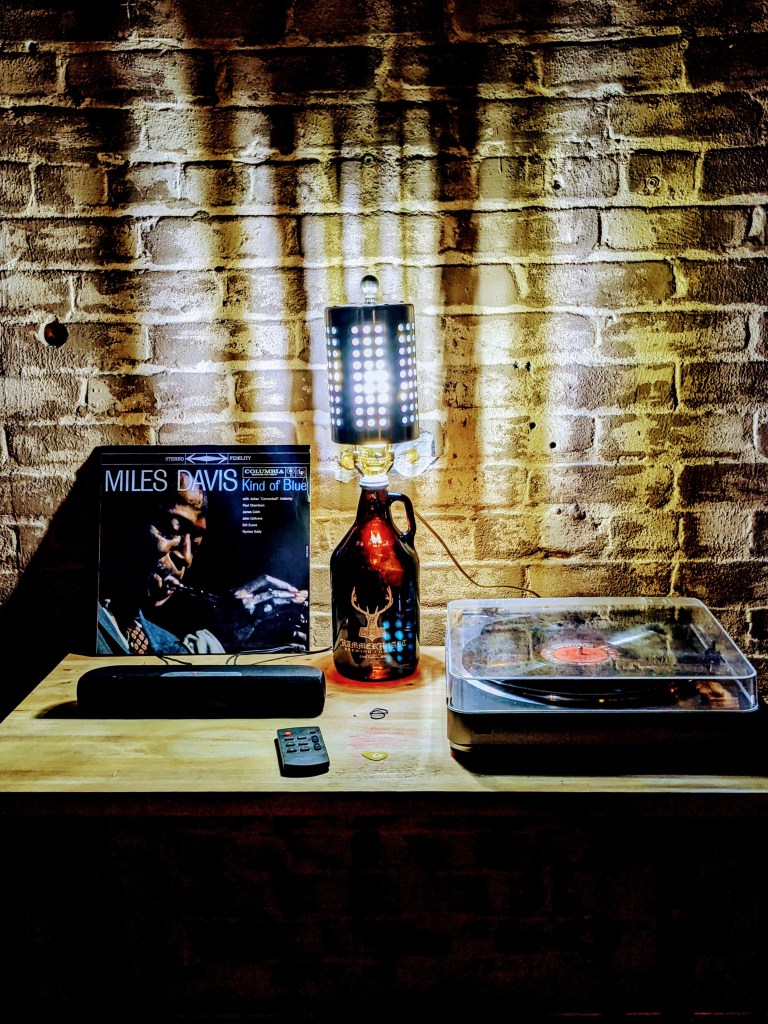

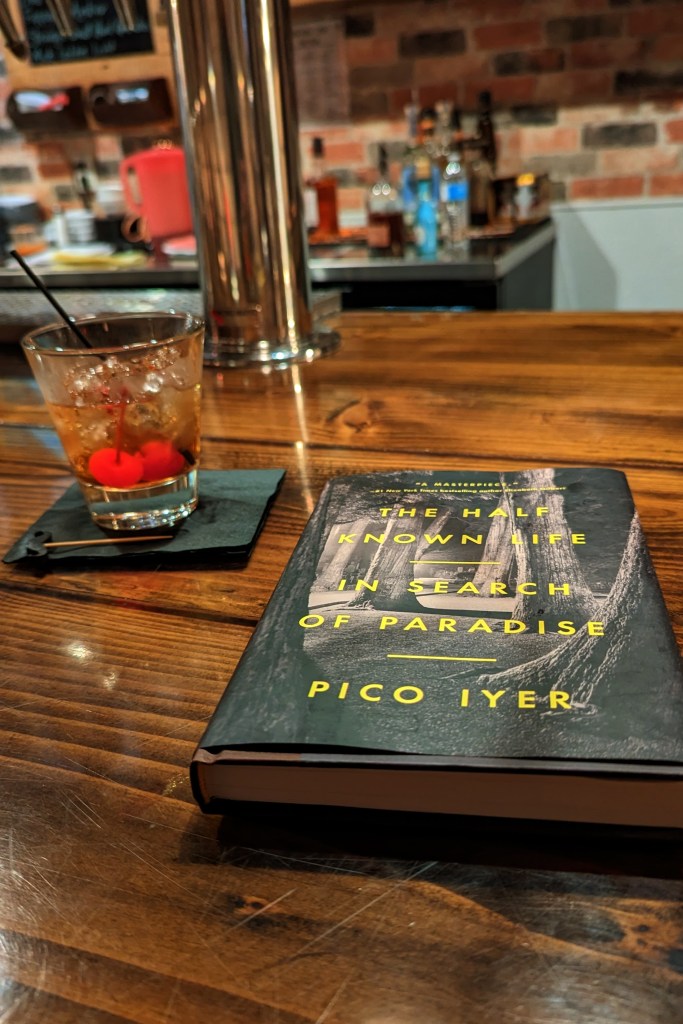

Washing down carne asada with a sticky-sweet IPA at the local brewery warmed me to the bones and replenished the energy I greedily consumed in the woods. Blissed out, I hunkered down with another beer and Pico Iyer’s latest book, The Half Known Life: In Search of Paradise. The premise of the book is that so many of the places considered paradise on earth are also now plagued with conflict. “[A]fter years of travel,” the author reflected, “I’d begun to wonder what kind of paradise can ever be found in a world of unceasing conflict . . ..” Moving from one self-proclaimed paradise to the next—Iran, Kashmir, Jerusalem, India, Japan—Iyer questions why the holiest, most cherished sites are marked by barricades and men with guns. How can he be that surprised, I thought to myself, considering his genealogy and the breadth of his travels? Born in the U.K. to Indian parents, Iyer knows the devastating impact of colonialism all too well. He should be full of the emotion his family name summons to mind: ire. Yet, I easily identified with him every time I read his books. Like me, he has a relentless desire to explore new places and discover unexpected moments with strangers and new situations. Despite that ever-present wanderlust, Iyer admits he himself still feels like a stranger in the world.

Sitting in the brewery in that small Minnesotan town, I was happy. But I couldn’t have been more lost either. I was doing what I loved. I was where I wanted to be. In fact, at that moment, I would not have preferred to be at any of the iconic destinations Iyer visits in his book—not drifting serenely in the houseboats of Dal Lake in Kashmir, not basking under the massive stone buddhas of Sri Lanka, or even experiencing nirvana in the Japanese monastery of Koyasan.

The thought of exotic locales sent me packing to watch the sun set over the downy-white surface of Huntington Lake. In the distance, light blue faded to a dull yellow before erupting into a fiery orange, the snow covering the lake settled into a glacial blue. By the time I got back to the cabin, it was a brilliant, ice-cold evening with Jupiter and Venus stacked together in the inky sky. I quickly lit a fire to bask in the celestial event.

Some scholars claim that the conjunction of the two planets would have appeared to have merged on the evening of June 17, 2 BCE, forming what the Wise Men in the Bible believed to be the Star of Bethlehem, two years after what is recognized as the birth of Christ and the line of demarcation for the Common Era. I rang up my brother in Portland to describe the brilliance of the duo, perhaps subconsciously sensing the religious import of the moment and wanting to commiserate with my brother about our lost faith. Venus, after all, was once called Lucifer by the Romans, the name meaning “light bringer” in classical Latin, and I identified more with the reference to a fallen angel than a guiding light.

I poured myself a hefty tumbler of scotch in the cabin and returned to the fire to regale my brother with a recap of the ride earlier that day. The scotch warmed and loosened my tongue, and I filled the phone with a rambling sermon in praise of my surroundings, while my brother, taciturn as ever, listened silently. My gab eventually gave way to hunger, and I ended the call to go grab a burger at one of the taverns in town.

After a short one-mile drive to the tavern, I parked in front and found my way to a hightop. It was close to 10, and the place was packed with locals. The place had a welcoming atmosphere, and I felt completely relaxed, so comfortable in fact that I thought nothing of ordering a scotch and a stout despite my copious consumption earlier that evening. Another scotch and stout later, and I was eavesdropping on the next table as a woman about my age told hilarious stories about serving in Kuwait. Everyone at her table was doubled over with laughter. I complimented her and asked if I could sit in on the next story. The group welcomed me to pull up a stool, and I ordered a round for the table. The storyteller, a nurse at the regional hospital, politely declined, bowing out after a long shift and leaving the table in a conversational lurch. As if on cue, a man a few years older than me, stepped in to fill the void, asking the usual questions . . . “Why was I in town?” “Do I visit Crosby often to ride bikes?” “What did I do back home?” With a pause and my slurred “What about you?” he responded that he worked with kids and adults with behavioral and developmental disorders. I told him about my time working at a children’s psychiatric facility in Kansas, and he relayed stories about his patients’ challenges.

The conversation soon dried up, but I hadn’t. Stumbling out of the bar and onto the sidewalk, I zigzagged my way to my lime green Subaru and slumped into the driver’s seat. I punched the ignition and the power button on the radio, threw the gear into drive, and roller-coaster-jerked my way into the lane, blasting classical music while swerving to the arpeggios. The lights of the patrol car behind me shattered my reverie. I panicked and hit the accelerator with a burst of adrenaline. The split-second outburst collapsed into quick capitulation, and I pulled over to the side of the road to accept my fate.

“Have you been drinking?” came the inevitable question.

“Yep,” I replied.

“How much?” the retort.

“A lot,” I admitted, dropping my head in shame.

“Step out of the car, please.”

Here we go! I thought to myself as I pulled my tall, lanky frame out of the car. The next thing I knew, the officer was shining a Maglite inches from my eyes and asking if I wore contacts.

“Fuck yes, I wear contacts!” I blindly bellowed. The blatant act of shining the flashlight so close to my face shocked and dazed me, which was most likely the officer’s intent. Instantly hostile, I could feel belligerence blossoming inside me. When the officer asked if I was willing to perform a few field sobriety tests, I challenged him.

“Like what?” I demanded.

“Just standard field sobriety tests,” he replied, adding to the uncertainty and confusion of the moment. Another officer suddenly appeared with his own Maglite held high, catching me in a crepuscular crossbeam. I slipped my hands into my jean pockets and was promptly ordered to remove them. I jerked them out and threw them up into the air.

“He’s asking you if you’re willing to do field sobriety tests to see if you’re intoxicated,” the second officer stated nonchalantly. “Are you going to comply?”

“Or what?” I heard myself saying.

“Or we take you to the hospital and perform a blood test there.”

“I don’t want to do that either,” I fired back.

“Well then, we’ll have to take you in.”

“Are we really going to do this?” I asked incredulously, baffled not only by what was happening but also at my cliched response.

“We’re really going to do this,” the officer replied before proceeding to frisk me and read me my rights.

Pushing my head down as he angled me into the back of the patrol car, I slumped into the seat and landed shoulder-first into a cage wall separating the back, unable to pull my legs completely into the cruiser due to the tight fit. I shifted as the officer closed the door causing it to bounce off my legs. He yelled at me not to push back, and I argued that the space was too tight.

“I’ve had bigger guys than you back there,” he chided, firmly shutting the door.

I sat in silence, trying to regain my composure before asking, “Where are we going?”

“Brainerd,” replied the officer. “Crow Wing County Jail.”

“I’ve never been to Brainerd,” I muttered. “Cool.”

He started recapping how reckless I was driving along the empty main street, and the only thing I could come up with was, “There was nobody out . . . the place was dead,” knowing it didn’t matter. So, I followed with, “Are you going to tell me you’ve never done anything like this before?”

“Drive drunk? No. My grandfather was killed by a drunk driver,” came the rebuke.

I sat in silence, stupefied. Eventually, I managed a feeble “I’m sorry.”

“About what?” came his reply.

“Your grandfather,” I responded guiltily. “Grandparents are bad motherfuckers,” I slurred, segueing into barely coherent stories about my grandfather serving in the Pacific Theater . . . meeting natives in Papua New Guinea that walked out of the jungle with massive machetes and missing limbs, of a family in the Philippines who welcomed him into their home. The memory of my grandfather telling me the stories when I was a young boy made me wistful and taciturn, and I sat in the squad car quietly ruminating.

The officer broke the silence by asking what I was doing in Crosby. I blathered on about it being one of my favorite places to ride and being sad that I probably wouldn’t return. When he asked why, all I could do was laugh.

We pulled up to the jail, and I was escorted to a desk where I was asked a series of questions about whether I consented to taking a blood test at the hospital and if I understood the consequences of refusing. I didn’t consent, and I didn’t understand. I was drunk, confused, and tired. Nothing made sense. And, yet, surprisingly, the woman asking the questions seemed baffled that I couldn’t cogently respond. Surely, they encountered this all the time. Seconds later another officer guided me into a room and told me to strip.

“Everything?” I asked, astonished.

“Yes,” he said, staring blankly back at me.

The gravity of the situation struck me the hardest when I felt the officer’s cold nitrile gloves clinically inspect my perineum and then hold my ass cheeks apart before handing me the requisite orange prison scrubs and a pair of cheap, knock-off Crocs.

“Would you like to make a phone call?” he asked. At this hour? I thought. “No,” I meekly muttered in response.

I was shackled by the wrists and ankles and escorted to an overly bright exam room where a nurse checked my vitals. “Your blood pressure is really high! Did you know that?” I shook my head no, amused at the thought of having normal blood pressure under the circumstances. I slumped my head again as I listened to the nurse talking to a doctor about my vitals. She told me the doctor was prescribing Klonopin and Ativan to help calm me and lower my blood pressure, but I later learned that it’s not uncommon for prisons and jails to routinely sedate aggressive and erratic inmates with benzodiazepines like clonazepam and lorazepam, the generic names of the drugs the nurse used to dope me.

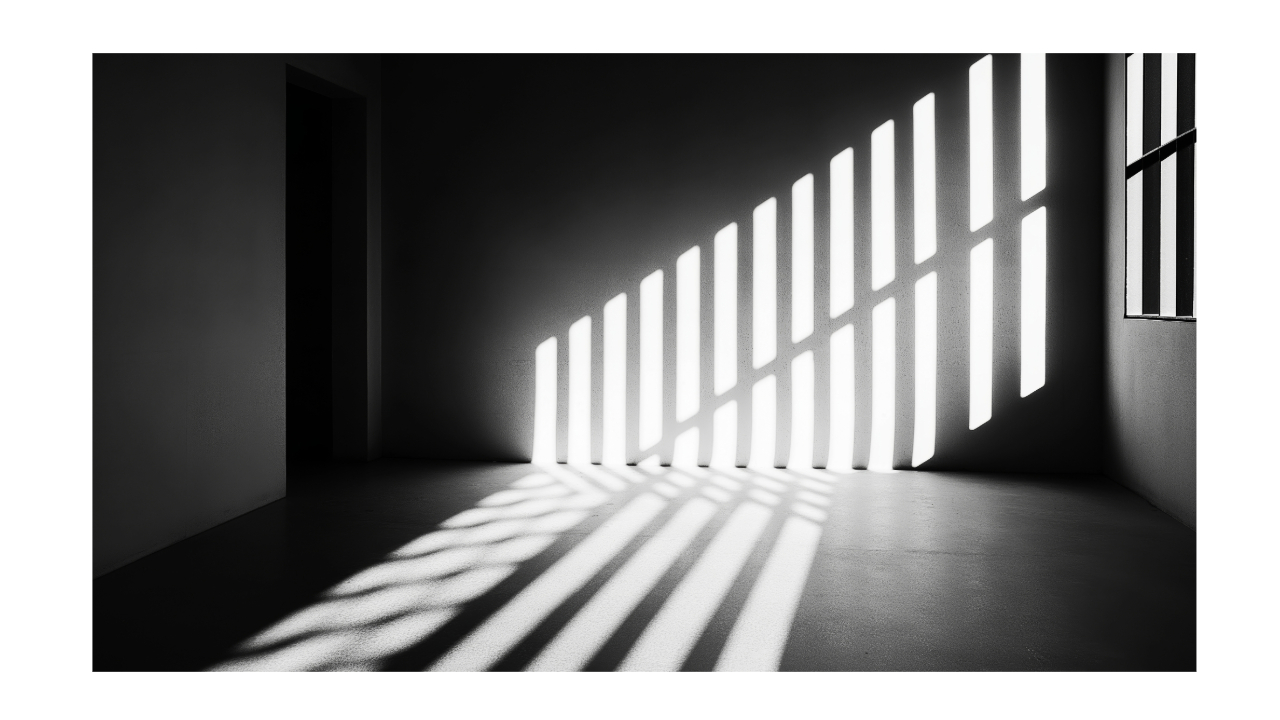

After the check, the guard helped me to my feet, and I shuffled behind him through a series of secured doors, down a long hall and into a large, dimly lit cell block that swallowed me in silence. “Panopticon, panopticon, panopticon,” I whispered to myself while I gazed around the three-story cell block in amazement.

My cell was at the back of the block, an area called Echo Unit. Beige cinderblock walls encased a stainless-steel sink and toilet that were spread apart like dog bowls on the kitchen floor. A small metal bunk with a thin, blue, vinyl mattress bracketed the back wall, offering no comfort whatsoever. Overhead, aquarium-hued fluorescent lights buzzed like a fly zapper. The guard told me to get some sleep, that someone would be back in a while to check on me.

Despair and the tragic events of the day forced me to the thin mat like the pulverizing move of a wrestler, and I was out cold. Hours later, I was startled awake by the jangle of keys clanging against the steel door, summoning the violent recoil of the lock. The guard gruffly ordered me to sit up for the first of what would be many breathalyzers throughout the night. I blew .29! At that level, it should have been very difficult to wake me up, but my 6’4”, 220-pound frame was used to metabolizing paralyzing quantities of alcohol. I crashed back on the mat and caught a few more minutes of sleep before the guard returned. Point two-one this time. Then, an hour or so later, a .16. “You’re staying put,” I’m told, “until you blow a .08.” Drifting back to sleep, an alarm soon blasted me awake, and fluorescent lights flooded the room. The bolt on my door recoiled violently again, and the guard asked if I want breakfast. I shook my head no and once more slipped into oblivion.

I drifted in and out of sleep throughout the day like a soldier recovering from shell shock with only the faintest notion of eating a dry white-bread-and-ham sandwich for lunch. Toward afternoon, the guard came back, and I blew .08. “Good,” she said. “Welcome back.”

The arresting officer came to my cell a few minutes later with a handful of paperwork. His report, I assumed. He told me he had tried to contact the judge to discuss my release, but considering it was Saturday, I might have to wait until Monday, when I would be placed at the top of the docket for a hearing. I nodded appreciatively, filled with contrition. He could tell that it was a new experience for me and projected an air of humility.

Now that I was back among the living, I buzzed the guard’s station and asked if I could make a phone call. I was given a handheld device that resembled a toy cell phone but provided no explanation or instructions. And the battery was almost dead. When I finally figured out how to navigate the BlackBerry-era, monochromatic display to make a collect call, I rang my wife. Straight to voicemail. Dammit! Is that my one and only call, I wondered. I tried again and failed again. The phone was out of juice, and I didn’t know if I would get another chance to call. I buzzed the guard again and asked what to do next. She offered to recharge it. An hour went by, and I buzzed the guard again and asked about the phone. This time, my wife, Paula, answered with a peppy hello. Clearly, she hadn’t listened to my message, so I explained the situation. “Oh, no! No, no, no!” came her response. Thinking it was my one-and-only call with the outside world, I asked Paula to call my boss and tell her I wouldn’t be in on Monday and then notify the resort where I was staying to explain the situation. It was only Saturday, and I had a long weekend ahead of me.

We said our goodbyes, and I scrolled through the phone to learn as much as I could as fast as I could, afraid the guard would quickly return to take away my only connection to the outside world. But I soon learned that I could keep the device, and I could call anyone as often as I wanted once I had money credited to the system to pay for the exorbitant per-minute calling costs. The device also provided me an account and access to the “Canteen,” where I could buy junk food and personal items, also at exorbitant prices. That’s when it hit me—how miserable it would be to be alone with no one to call and transfer money into your account for the simplest of items like a pillow or deodorant. My wife’s phone number was the only one I remembered, and there was no internet access on the device. If I didn’t have her, chances are I would have no one to contact for help. Commit a bigger crime with a longer sentence, and you could easily lose your job, be evicted, and completely disappear behind bars—a sobering reminder of how easy it is to lose everything based on one bad decision.

As I sunk deeper into depression at the thought of being locked up with no one to help me, my cell was unlocked, and a female guard looked in and told me to grab my things, that I was being transferred to another area. I bundled up my sole possessions—a towel, a sheet, a cup, and a toothbrush—and followed the guard out of the cell block. I was led to another cell block and passed off to a guard who looked like Bob Odenkirk, who shot me a friendly smile and led me to my new cell at the very back of the block. I couldn’t help but wonder if they were trying to keep me out of sight to avoid interaction with the other prisoners. They clearly thought I was aggressive and possibly hostile since they kept me doped on Klonopin and Ativan. It seemed audacious for a small county jail in Brainerd, Minnesota, to drug inmates like me with benzos as a matter of course.

A year later, I came across an article about a 57-year-old man named Robert Arthur Slaybaugh who died in the Crow Wing County Jail after being jailed for a DWI in Brainerd, the second inmate death at the jail in six months. At the time of this writing, the cause of death was still pending autopsy, but it’s hard not to assume that the correction officers drugged Robert like they did me, ultimately bringing his heartrate to a dead halt. It crushed me to read that Bob loved the outdoors and worked as a camp director for 36 years, helping campers with cognitive and developmental disabilities. “There wasn’t a camper that walked the grounds that didn’t love Bob,” his obituary read. “His love for them all was a genuine blessing to the community and beyond.”

Later that evening, dinner was brought to my cell: a dry baloney sandwich with cold potato salad and applesauce. So, this must be what humble pie tastes like, I thought to myself as I ate in silence. After the guard collected my tray, I called my wife. She asked if I wanted to speak to the kids, and I felt shame well inside again. I said “yes” and swallowed hard at the sound of my son’s voice. I told him how sorry I was and that I would try to be better. I cracked a joke about the food, and he played along. My daughter was more reserved. I joked about my orange prison scrubs being my ideal uniform, and she let out a little laugh. (She likes to tease me about wearing too much orange.) I was surprised both kids were so comfortable talking to me about the circumstances. They had experienced a lot of grief in our household—drunken behavior, depressive episodes, vicious arguments—but this was a first. Of course, their mother had told them about the situation beforehand to lessen the shock.

As soon as she was back on the phone, we made plans for Paula to drive to the resort to pick up my things, drop off my glasses at the jail, and pick me up once I was released. Before we hung up, I apologized for my actions and promised to do better, to be better.

The guard gave a knock on my door and alerted me to my next med check. He escorted me to the nurse’s room, where my pulse and blood pressure were taken again. My heart rate was back to normal, and they gave me my regular dose of citalopram followed by new and unwanted dose of Klonopin and Ativan. I’d been without the antidepressant during the first two days of my incarceration, and I was worried about potential side effects, especially with the addition of the two benzodiazepines.

After I’m led back to my cell, Bob told me to grab my things because I was moving again, this time to a room with a special name that I now can’t recall, something like “The Cube.” A 2021 audit of the jail that I later found online referred to it as a “sub-dayroom,” with two cells and a shower that are behind a glass wall that looks out onto the community room where inmates gather to socialize or watch TV. The area had been designed to give residing inmates more space while remaining deliberately separated from the general population.

Bob told me I had 30 minutes to use the general area in my glass cage and asked if I wanted my cell door open or closed. I opted to leave it open so I could catch a glimpse of the TV. Inmates on the other side of the cage gathered to watch a movie that didn’t interest me, so I gave Bob a buzz and asked if I could take a shower. The glass cage had a locked shower the guard had to unlock from his station, so at least I didn’t have to worry about dropping the soap or having any inmates offering to “get my back.” I hadn’t had a shower in two days, and the warm water relieved some of the stress I’d been harboring, even though the shower stall door left my head and feet exposed to everyone in the common area.

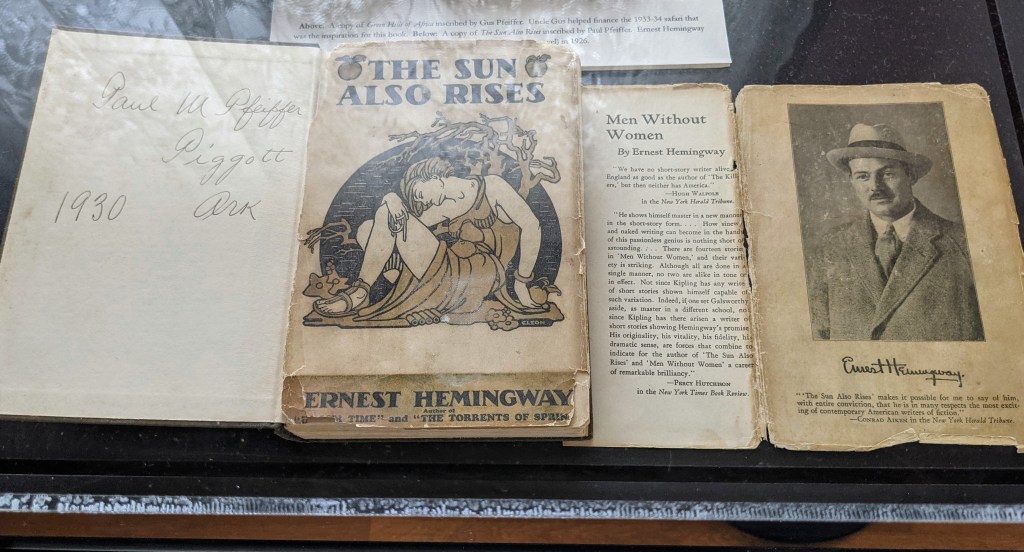

Rinsed of my stench and shame, I gave Bob another buzz and asked if there was any reading material available. A few minutes later, he swung by with a tattered Tom Clancy paperback, a John Grisham paperback, and a large-print edition of the King James Bible, all three with “Property of Crow Wing County Jail” stamped on the fore-edge. “Your pick,” he said, fanning the books before me like a street vendor. I chose Clancy—Splinter Cell: Checkmate—with a smirk and wry acceptance of my current situation and thanked Bob before retreating to my bunk to read. I’m an avid reader of fiction and non-fiction alike, but I’m no fan of pulp thrillers, mysteries, and fantasies that place entertainment over enlightenment. But I desperately needed a distraction, and the ridiculous reconnaissance of Sam Fisher, the main character, was enough to take my mind off the circumstances.

The Cell Block Meets Eastern Bloc

Delving into the melodramatic world of international espionage, I thought back to the only other time I’d been taken into custody. It was in Sofia, Bulgaria, in 1996. A group of friends and I, all recent graduates from a college on Route 66 in Oklahoma City, were walking through Sofia’s Battenberg Square on our way back to our apartment block from Kentucky Fried Chicken. Rudy, a native of Tampico, Mexico, was sporting a fedora and a Hawaiian shirt unbuttoned far enough down his chest to reveal a gold medallion of the Aztec calendar perched in a nest of black chest hair. Ted, a lifelong resident of Bethany, Oklahoma, was in tow, wearing his usual uniform—a shirt from our alma mater, Southern Nazarene University, tucked into acid-washed jeans. Dale, another resident of Bethany donning similar attire to Ted, was in lockstep with the group, only with lanky strides that resembled a rubber house cartoon character. Borderline emaciated due to health issues, Dale’s slight build barely seemed to support his giant head with its prominent dimpled chin, 1980s-style Coke-bottle glasses, and a helmet of Brillo-like brown hair that could put any televangelist to shame. And then there was me, a skinny, preppy wannabe decked out in J. Crew attire and rocking a brownish-blonde butt cut.

Strolling along and joking about all the mafia bodyguards and their sexy girlfriends gnawing on corn on the cob and deep-fried chicken from KFC, we were alarmed by the sound of a police siren behind us. We turned around to see a police truck approaching and heard an officer blurting out, Vasichki sprete! (“All of you, stop!) over the loudspeaker. We froze in our tracks. We had been in the country for nearly a year and had only a week to go before returning to the States, and we were finally experiencing our first run-in with the local police, whom we’d been warned to stay clear of by Bulgarians and foreigners alike due to their penchant for extorting bribes. Three police officers jumped out of the truck and demanded our passports, which, of course, none of us had on us. Rudy, the most fluent in Bulgarian, explained the situation, but the police were having none of it. They were taking us to the station, and we would stay there until we could procure our passports. The next thing we knew, we were being loaded into the back of the police truck and being whisked through Sofia with sirens blaring.

At the police station, which happened to be right down the street from our apartment block, an officer lined Dale, Ted, and me along a wall and handcuffed a wrist on each of us to a bar above our heads. Rudy was taken to a nearby interrogation room, where we watched him struggle to answer a young officer’s questions in a third tongue. A guard sitting behind a podium with a McDonald’s golden arches sticker in the corner glowered at us as if we were hardcore felons. We decided to bide our time by playing a game of Rock Paper Scissors with our free hands. That only irritated the guard further, causing him to bark out some Bulgarian remonstration none of us could understand except for the phrase Glupavi Amerikantsi! (“Stupid Americans!”). A few minutes later, Rudy and his interrogator stepped out of the room, and Rudy informed us that he was heading to the apartment with two officers to collect our passports. That scared us since our Nigerian friend, Uz (as in “ooze”), was staying at our apartment for a few days while looking for a new place. Uz, or Uz the Blues as we called him, had been beaten up by Bulgarian officers that year, and we were worried they might use the situation as an excuse to arrest him under false pretenses.

Rudy was back in no time with everyone’s passport but mine. I had hidden it so well, he couldn’t find it. Had he found it, he also would have revealed the $1,000 in cash I’d stashed with it to travel to Italy and Austria the following week. If the officers spotted the cash, they may have been all too happy to seize it. Instead, Rudy brought my AAA international driver’s permit—a simple, bi-fold cardboard document with my picture glued on to match my scant personal details. Surprisingly, we were released from custody, and I couldn’t help but laugh as Rudy handed me my permit. That triggered a fit of rage from the guard who launched into an angry, incomprehensible tirade inches from my face. But the young officer announced we were free to go, and we walked back to our apartment block slightly bewildered and eager to reconnect with Uz, who remained safely sheltered on the sofa.

Those memories came flooding back as I read the ridiculous spy thriller on my third day in Crow Wing County Jail, desperately awaiting my hearing the following morning. By the time dinner rolled around, I had the luxury of dining at the park-style picnic table mounted to the floor outside my cell in the glass cage. I felt like a pariah eating dinner at the table in full view of the other inmates dining in the community room, like Hannibal Lecter in Silence of the Lambs or Billy Pilgrim in the zoo in Slaughterhouse Five.

And Now . . . Back to Reality

Later, when a new guard stopped by with my meds, I asked him why I had to take the sedatives, that I was concerned about the side effects of the drugs. He simply stared blankly back at me and said they were the doctor’s orders. I could either finish taking them the final day before I was released, or I would be placed with the general population, pointing to the community room where the other inmates appeared to be enjoying cards and conversation. “If I were you, I would just take them,” he concluded. “You’ll be more comfortable in here.” So, I gulped them down and lifted my tongue, per the arrangement, to prove I was doing as I was told.

Retreating to my cell, I sprawled out on the floor to stretch out the tension in my back and shoulders caused by the shitty mattress. Within minutes, another guard, this one female, peeked in and asked what I was doing. “Just a few stretches,” I explained as she motioned me up for my final med check that evening. She led me to the guard’s station in the community room and lightly frisked me, appearing reluctant to pat me down, before guiding me to the nurse’s exam room.

My blood pressure and heart rate had dropped significantly due to the Ativan, and for the first time since my arrest, I got to remove my contacts and put on my glasses that my wife dropped off at the station an hour earlier.

As the guard led me back to my cell, I asked about my hearing the next morning. He told me that I was on the docket at 9:15 in the morning, right after breakfast. It couldn’t come soon enough, I thought to myself, as he closed the cell door behind me. I called my wife and thanked her profusely for all she’d done. I had been harboring resentment toward her for reasons I won’t disclose here, so it was difficult to be entirely dependent on her at that moment. Regardless, I told her I loved her and, like every washed-out middle-aged man who’s been broken and busted, limply added that I would be more responsible in the future.

My call was interrupted by the guard’s 10-minute warning before “lights out,” so I closed my eyes and focused on my breathing to clear my head, meditating my way to sleep and a fresh start after tomorrow’s hearing. My sleep that evening was wracked with dystopian nightmares in which I was trying to navigate my way through an endless wasteland of abandoned warehouses, not knowing how I got there or where I was, all the while enveloped by a sinister presence.

I awoke the next day to the buzz of fluorescence, another massive pang of shame, and a guard’s curt announcement that breakfast would be ready soon. I stepped outside my cell and into the cage where a tray of cereal, fruit, and juice awaited. Am I in jail or kindergarten? I joked to myself. Judging by the voracity with which the men on the other side of the glass shoveled spoonfuls of cereal into their mouths, I was leaning toward the latter.

The morning guard stopped by a short while later to give me my benzos, which I had learned to take like a good little prisoner. The drugs worked their magic, and I was out cold in minutes. I was suddenly awakened to the ring of the phone. “Where are you?!” my wife pleaded. “It’s 9:20! You were supposed to appear before the judge at 9:15!”

I immediately buzzed the guard and told him I was supposed to be at my hearing, angry that they would have let me sleep through it without a second thought. The guard came to retrieve me somewhat lackadaisically, and we made our way to a video room where my wife, attorney, and the judge stared back at me from the screen. The rest was boringly procedural (thankfully), and the judge released me with no bail and on probation until my sentencing.

The Crow Finds His Purpose

Safely at home, the instructions from the attorney were very clear: Before the sentencing, stay out of breweries, bars, and liquor stores; take an alcohol abuse assessment; and complete a MADD Victim Impact Panel. The last assignment was offered by Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) and was intended to help “drunk and drugged driving offenders understand the lasting and long-term effects of substance impaired driving.” It was a series of video interviews from people who lost loved ones to drunk and drugged driving that was deliberately designed to thoroughly shame viewers from ever committing the crime again—and rightfully so.

The testimony that hit me the hardest was by a mother who recalled experiencing unimaginable grief when she entered the morgue to identify her daughter’s body and was forced to wait behind a “long, white curtain.” The purity of the curtain as a shroud of immortality that concealed the reality of death was a powerful symbol. Graver still, the mother’s daughter was pregnant when she died, leaving the poor grandmother to lament the loss of not one, but two, lives. The pain was palatable.

My shame only grew more intense after watching the officer’s bodycam footage during the arrest and seeing how sloppy drunk and slurred of speech I was. The guilt prompted me to write a letter to the officer apologizing for my behavior. “Crosby is one of my favorite places to visit for biking and spending time with my family,” I wrote. “And the last thing I want to do is to put locals at risk or ostracize myself. In fact, one of the best qualities of the area is how peaceful and safe it feels.”

I sent the letter to my attorney, he added it to my case file, and I bided my time with non-alcoholic beer and lots of bike riding and hikes until my final sentencing three months later. Lucky for me, the harsher of the two counts, refusing to consent to a chemical or breath test, was dismissed, leaving me with a Fourth-Degree DWI conviction. The judge ordered me to pay a $610 fine and sentenced me to 90 days in the Crow Wing County Jail, officially stayed for two years on unsupervised probation. As long as I don’t get arrested for the same or a similar offense during that time frame, I would avoid an all-inclusive return trip to the glass cage.

Back in the Nest

The one-year anniversary of my sentencing has now passed, and I’ve been mulling over the lessons learned. Like Aandeg the Crow, I felt like I had no purpose when I was arrested for a DWI, but rather than searching out ways to see beyond my own nearsighted needs, I chose to fly headlong into clouds of alcohol-induced haze where I could remain temporarily shrouded from my worries and fears.

“There are but few important events in the affairs of men brought about by their own choice. Recognizing how much lay beyond my knowledge was what made space for growth and surprise, and kept me usefully in,” Pico Iyer writes in The Half Known Life. I clearly brought about these series of events by my own choices and actions, but that search for something more has led to growth. And, if I hope to retain any sense of magic and wonder in that snowy landscape where I ended up behind bars, I’ll take heed in Iyer’s discovery that “[a] true paradise has meaning only after one has outgrown all notions of perfection and taken the measure of the fallen world.” During those three full days in jail, I took measure of my failures and realized the true freedom and bliss of riding my bike through the woods on a snowy day. To me, that’s paradise.

I typed the last words of this essay at a writing studio in downtown Minneapolis on the one-year anniversary of my arrest, gazing out at the fluorescent purple glow from the Vikings football arena. On my way out, I fed two quarters into a poetry gumball machine stationed in the lobby to raise money for the Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop. A plastic capsule plopped in the machine’s metal mouth. I cracked it open and untied the tiny scroll inside: a poem by Larry Levis called Make a Law So That the Spine Remembers Wings. I stand there and read . . .

So that the truant boy may go steady with the State,

So that in his spine a memory of wings

Will make his shoulders tense & bend

Like a thing already flown

It was time to fly on.