The first time I saw the actor Kevin Bacon riding a bike around a loft in the movie Quicksilver I knew that I wanted to live or work in a space like that one day. Bacon is a bicycle messenger in the movie, and the thrill of dodging delivery trucks, encroaching taxis and car doors during the day and then retreating to a wide-open, warehouse-sized space to ride laps inside was almost too good for my 13-year-old freestyle-riding self to imagine.

My loft fantasy reached a fever pitch during my dorm-room days in college during the ‘90s. I was 6’4” and gangly, and whenever I scurried about my shared room of less than 200 square feet, I felt like a Great Dane hunting for the last bit of kibble in a tiny kennel.

I’ve lived in small apartments and homes ever since then. All of my places have had tiny bathrooms, too, requiring some level of contortion to safely position myself on the toilet. Imagine Houdini trapped in a tiny bathroom. I frequently fantasized about owning a big loft where I could take care of business without nearly dislocating my soldier trying to reach the place “where the sun don’t shine.”

The desire for my own private space also coincided with my desire to be a writer and my burgeoning love of Existential literature. At the time, I pictured myself as the narrator in Dostoevsky’s Notes from the Underground, or the literary equivalent in Ellison’s Invisible Man – hunkered down in a crudely lit basement, writing screeds about the shortfalls of society, then setting out on long, lonely walks like Kierkegaard in Copenhagen. An airy, well-lighted space was antithetical to the artificial image I had constructed for myself.

If it wasn’t for Covid and months on end of being cooped up at home with cranky kids and a dog that barked at every living thing that moved in the big, bad world beyond the picture window, I might be typing this from a windowless, subterranean, claustrophobic studio instead of a second-story, 30-by-30-foot loft with a 16-foot-high exposed ceiling and a bank of six-foot-tall windows that flood the room with depression-fighting natural light. But here I am, sitting at my cheap IKEA desk in the corner of the room, gazing across an uneven, well-worn wood floor oily in appearance and anchored by two massive posts, like a captain looking out at his ship’s deck. In the opposite corner is a partial kitchen cordoned off by French doors – my galley. There’s also a small enclosed office space with French doors that shares a wall with a recently tiled bathroom, which fills with the soft glow of filtered light from a frosted skylight. The walls to the south and east are beige brick sloppily tuckpointed with light-tan grout. Behind me, to the north, is fresh white drywall that separates the loft from the hallway dividing the building in two.

I am more than grateful to have a space like this, and I will enjoy every minute of it for the two or three months that my finances permit. Like everything else in life, the loft was the result of the right connection. A friend from my weekly evening night bike ride, a commercial real estate developer, offered me the unoccupied loft space in a building he owns in Northeast Minneapolis at a “friends and family” rate. Located above a vegan food supplier and a supper club closed due to Covid, the space previously housed an office. Now it houses an unemployed writer.

Every time I punch the code into the outside door and walk up to the loft, creaking my way up the wooden stairs covered in a faded, trampled faux-Persian runner, a smile surfaces from deep within, pumped out by the sudden spike in my heartbeat, and I shake my head in surprise that I finally have someplace, for however briefly, to sit quietly and write without distraction. I barely even notice the shrieking and ripping of tape as staff at the vegan “butcher shop” below box up orders of meatless ribs and roasts, faux chicken and cheeses.

In a city struggling with a shortage of affordable housing, I know that I won’t be able to keep this space for long. During a recent weeknight bike ride, a small group of us stopped at the loft to gorge on some carry-out tacos and beer. As soon as we entered the space, one of the riders, a cardiologist, blurted out, “I want a studio!” A short while later, another rider showed up, this time a database analyst with a fortune 500 company. He immediately wanted to know if the space was available for residential lease. I could see the lust in his eyes.

Aloft, the Writer Dreams of Better Days Ahead

In Bird by Bird, Anne Lamont writes:

Every room gives us layers of information about our past and present and who we are, our shrines and quirks and hopes and sorrows, our attempts to prove that we exist and are more or less Okay. You can see, in our rooms, how much light we need – how many light bulbs, candles, skylights we have – and in how we keep things lit, you can see how we try to comfort ourselves. The mix in our rooms is so touching: the clutter and the cracks in the wall belie a bleakness or brokenness in our lives, while photos and a few rare objects show our pride, our rare shining moments.

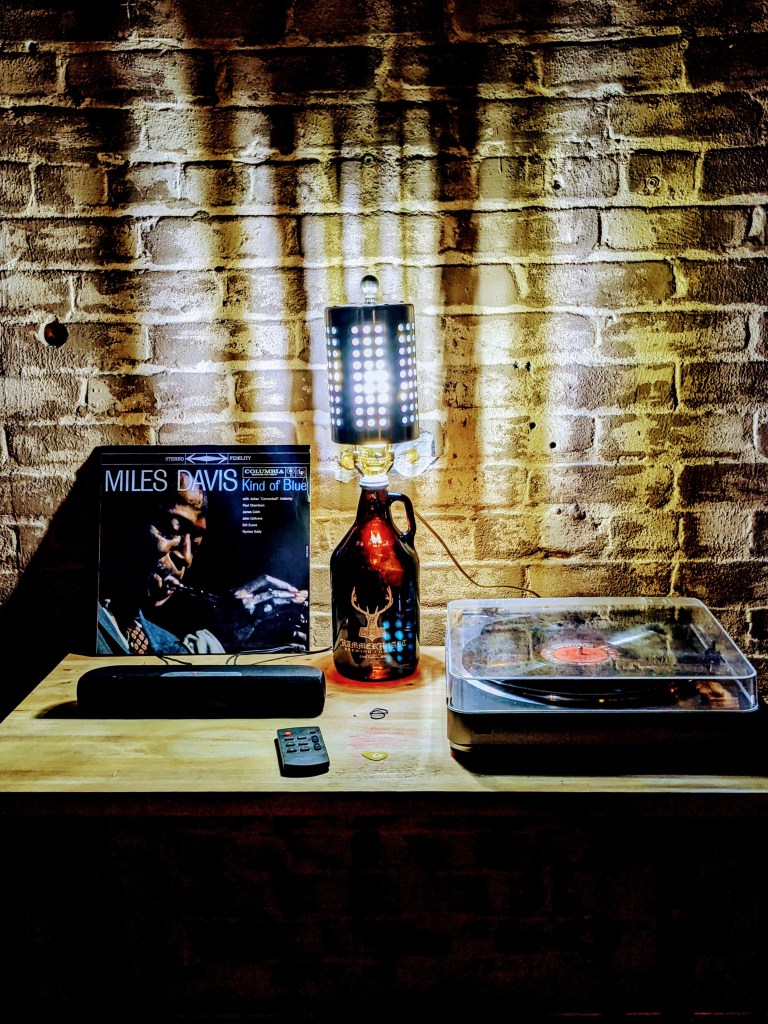

I have few objects in my studio to show my pride (pictures of my family, favorite records, my guitar), but I’m discovering new, intangible shining moments each day. Like the importance of sitting in the stillness and concentrating on my thoughts. Or the joy of meditating on an idea without interruption and then typing out that idea to contemplate later. Taking a break to stroll across the room and gently strum a few chords on the guitar before resuming work. Or sitting in the middle of the room with a glass of whiskey while the shrill notes from Miles Davis’ horn on Kind of Blue fill the empty room with breathy blasts of emotion.

It may seem like twisted logic to crave more alone time during a pandemic, when we find ourselves cooped up at home and apart from our friends and extended family. Stay-at-Home orders have literally and figuratively masked the significance of personal space, making regular reprieves from the routine more valuable even as the options to occasionally get away for a short while become more difficult. I can hear the naysayers asking, “Why would you want to be alone more than you are already forced to be?” My answer to that is simple: As a writer, I’ve always needed it. As an unemployed parent of two kids always at home due to Covid and distance learning, I need it more than ever!

Searching the internet for research to challenge what might otherwise be perceived as a narcissistic indulgence, I came across an article posted on the Cleveland Clinic’s website. “As much as we love spending time with our family, we all need a little space, pandemic or not,” the article advised. “Rising COVID-19 numbers and the idea of being cooped up for the next five or six months only add fear and anxiety. And on top of all that, many people have seasonal depression this time of year.”[i] Granted, having a separate, private space to one’s self is rare and privileged. In the end, though, it costs me less than therapy, which I very much would have needed without the space.

Additional justification came from an article written by Diana Raab in Psychology Today:

Joseph Campbell (1988) also spoke of the importance of having a sacred space—a place without human contact, a place where you can simply be with yourself and be with who you are and who you might want to be. He viewed this place as one of creative incubation, saying that even though creativity might not happen right away when you’re in this special space, just having it tends to ignite the muse in each of us. In his book The Power of Myth, he said that such a room is essential for everybody. In that room, “you don’t know what was in the newspapers that morning, you don’t know who your friends are, you don’t know what you owe anybody, and you don’t know what anybody owes to you” (p. 115).[ii]

In this space, it’s just you and your imagination. Or, rather, it’s a sort of hero’s journey, as Campbell would have it, in which the writer sets out on an adventure, encounters trials, triumphs and returns home transformed with greater wisdom than before.

Writers such as George Bernard Shaw, E.B. White and Virginia Woolf would all agree. They are the more notorious cases who required their own private space to do their work. But there are many, many others. Jack Kerouac traveled all the way to a cabin in Big Sur to sober up and write, and his opening description of the walk from the cab to the cabin is one of the most visceral bits of narrative I remember. More recently, Karl Ove Knausgaard comments on the privacy he needed for writing in the second book of his six-book memoir, My Struggle: “I had written my debut novel at night, got up at eight in the evening and worked right through until the next morning. And the freedom that lay in it, and the space the night opened was perhaps what was necessary to find a way into something new.”

As I type this sophomoric essay and think these lofty ideas inside a warm space on a dreary-white Minnesota afternoon, I realize how lucky I am. So, I’m going to enjoy every second I have. It takes me back to the days after college, to the office where I worked in Sofia, Bulgaria. I’d stay late at night after teaching an English class, listen to John Coltrane and write stories about what I’d seen and experienced. I still haven’t shared those with the world. I would like to. There’s so much humanity in those experiences: personal connections with abandoned Romany orphans, food and drink shared with devastated pensioners abandoned by the collapse of Soviet communism, has-been Bulgarian mobsters stalking naïve missionaries from Oklahoma – occasionally thwarted by the quick thinking of a jovial soccer player from Tampico, Mexico.

A space like this gives me room to start working on that, 25 years later. And, in the process, rediscover what it means to connect with what I once imagined was possible.

[i] https://health.clevelandclinic.org/too-much-family-time-during-the-pandemic-heres-how-to-cope/

[ii] https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-empowerment-diary/201711/room-our-own